The influences of infant-directed reading

and singing on word learning

Jasani & Moore & Bergelson (2018)

Presented at ICIS 2018 in Philadelphia, PA

Abstract

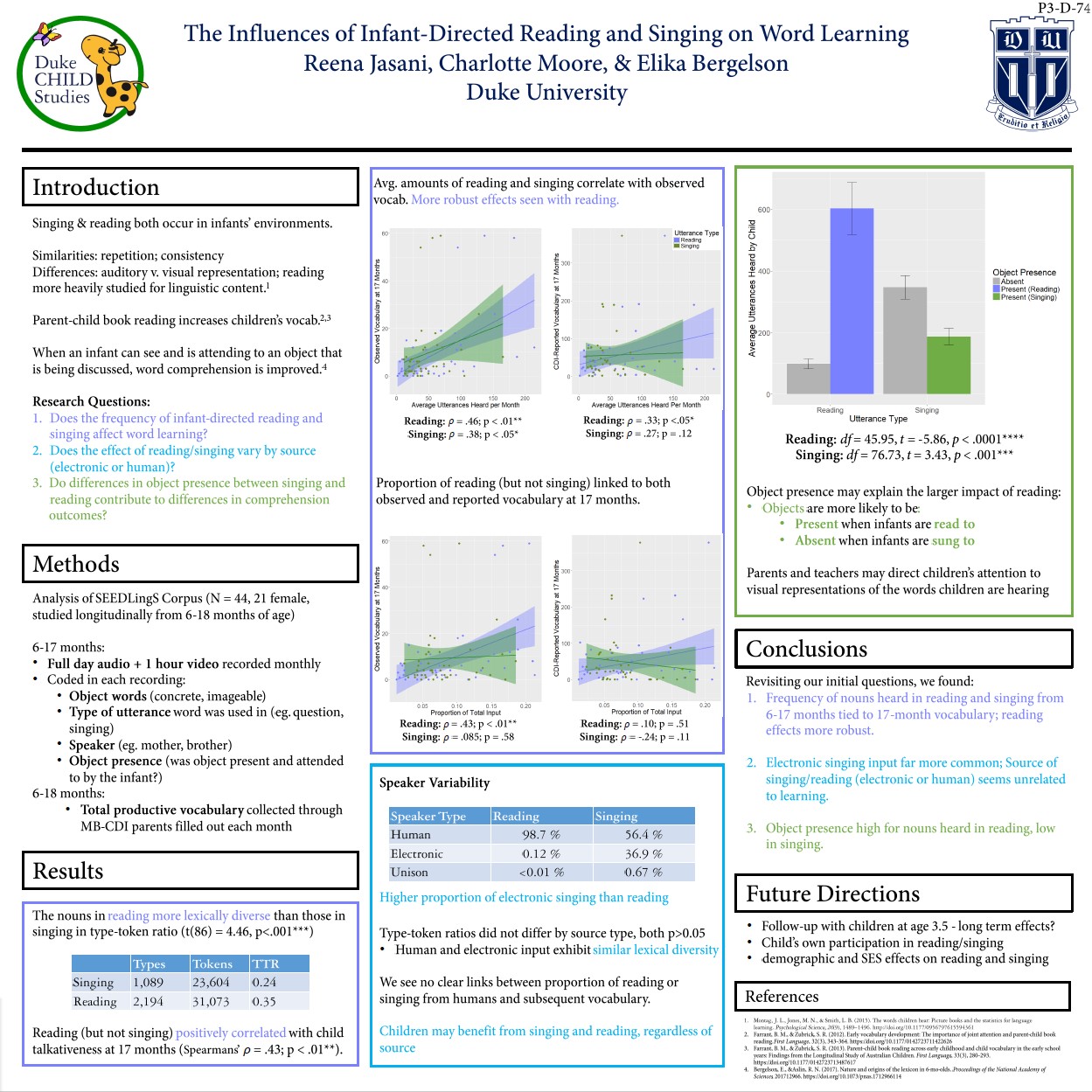

Infants must learn language entirely through listening to their surrounding linguistic environment. Previous work has shown that parent-child book reading increases children's vocabulary (e.g. Farrant & Zubrick, 2012; 2013). Reading has many properties that could be responsible for this boost. First, books often include pictures of the objects they refer to, providing visual access to named objects and facilitating word learning (Arlin et al., 1978). Furthermore, books provide repetition of the same words and syntactic structures upon multiple readings, aiding learning (Horst, Parsons, & Bryan, 2011). Input source also affects word learning, with Kuhl et al. (2003) reporting that 9- to 10-monthold infants learn better from live humans than recordings. Reading and singing share many features. Like reading, singing captures the attention of both speaker and listener, directing attention to the same words, concepts and/or images. Further, both involve repetition of words and ideas that are consistent over time and context. Despite similarities, singing has not been extensively investigated for its effects on word learning. 189 This study aims to fill this gap by comparing reading and singing effects on infant vocabulary development. We examined how the relative frequency of different utterance types affects word learning, how these effects varied by input source (electronic or human), and whether the differences in reading's and singing's effects related to whether words' referents were visually observable, i.e. 'object present'. We used the SEEDLingS corpus, a longitudinal collection of monthly naturalistic audio- and video-recordings from 44 infants between 6-17 months. This corpus includes all object words spoken to and by the infant, what utterance-type the word occurred in, whether the object was present, and the speaker. We analyzed infants' object-word input from reading and singing utterances, using children's own word production at 17 months as the outcome measure. We separately examined the number of nouns heard in reading and singing, and the proportion of the total noun input these utterance-types made up. Reading had increased lexical diversity relative to singing (reading type-token ratio=0.54; singing=0.40) and a higher proportion of object presence (t=-9.74, p<.001; Figure 1). Both the quantity and proportion of reading infants heard correlated significantly with their own 17-month production (Spearman's ⍴quantity=.37; ⍴proportion=.32; both p.05). The source of the singing or reading input (i.e. human vs. electronic), did not predict 17-month total child utterances (⍴=.10-.14, ns). Reading appears to benefit vocabulary development and speech production more directly than singing, despite sharing many features in common. The greater lexical diversity, in addition to the greater object presence in reading may explain reading's advantage. These findings further support claims that reading improves vocabulary development, and shows that with these utterance types, electronic sources of input may be equivalent. Thus, these results reiterate a key role for reading in the early input, and add the novel result that singing input too is linked with infants' language production.