The neural substrates of word-learning

in 14-20-month-olds:

a replication and extension

Fernandez, Campbell, Bachman, Woldorff, & Bergelson (2021)

Presented virtually at IASCL 2021

Abstract

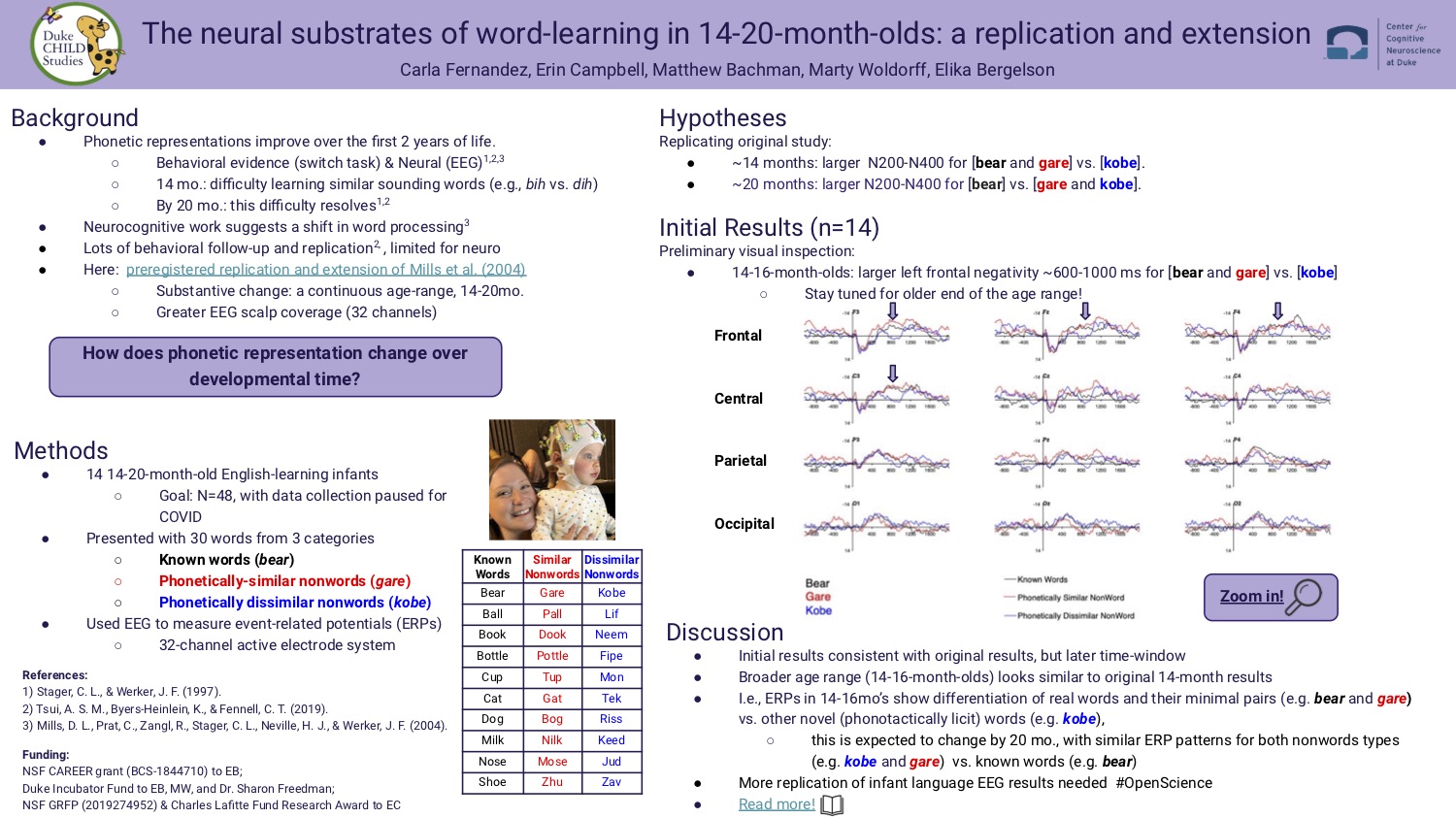

Over the first two years, typically-developing infants’ vocabulary increases, and their phonetic representations of words are refined. Initial difficulties in learning similar-sounding words in behavioral studies support this narrative. Neurocognitive studies have focused on the underlying neural substrates underlying these changes. While a robust behavioral literature has examined this process, few efforts have aimed to replicate and extend the neurocognitive results. Filling this gap, we report on a preregistered replication of Mills et al. (2004), with one substantive change: a continuous age-range (rather than the original’s 14- and 20-month group), with a planned sample of 48 14-20-month-olds (24 in each half of this age-range).

Following the original, we used EEG to measure event-related potentials (ERPs) in English-learning infants who heard 30 words from three categories: known words, phonetically-similar nonwords, and phonetically-dissimilar nonwords (e.g. bear, gare, and kobe, respectively). The original study found 14-month-olds showed an increased N200-N400 to known and phonetically-similar nonwords, relative to phonetically-dissimilar words. In contrast, 20-month-old’s N200-N400 for known words was larger than for either kind of non-word. We predict the same pattern over the 14-20 months in planned median-split and continuous-age analyses. Preliminary visual inspection of n=14 infants in the younger half of the range reveals a larger left-lateralized frontal negativity in the 600-1000 ms time window in response to known and phonetically-similar nonwords relative to phonemically-dissimilar nonwords. This is consistent with the original results, though in a substantially later time-window; data collection is ongoing with statistical analysis awaiting the target sample size. This study contributes to word-learning research in two key ways: it aims to replicate important previous work, bolstering our evidence base regarding word-learnings’ neural underpinnings, and queries whether there is a continuous representational shift in what is generally construed as a qualitative change over two snapshots across developmental time.